Around 40 Gainesville residents attended a private presentation at the Matheson History Museum on Wednesday, which advocated for the preservation of three historic downtown buildings set to be demolished in June.

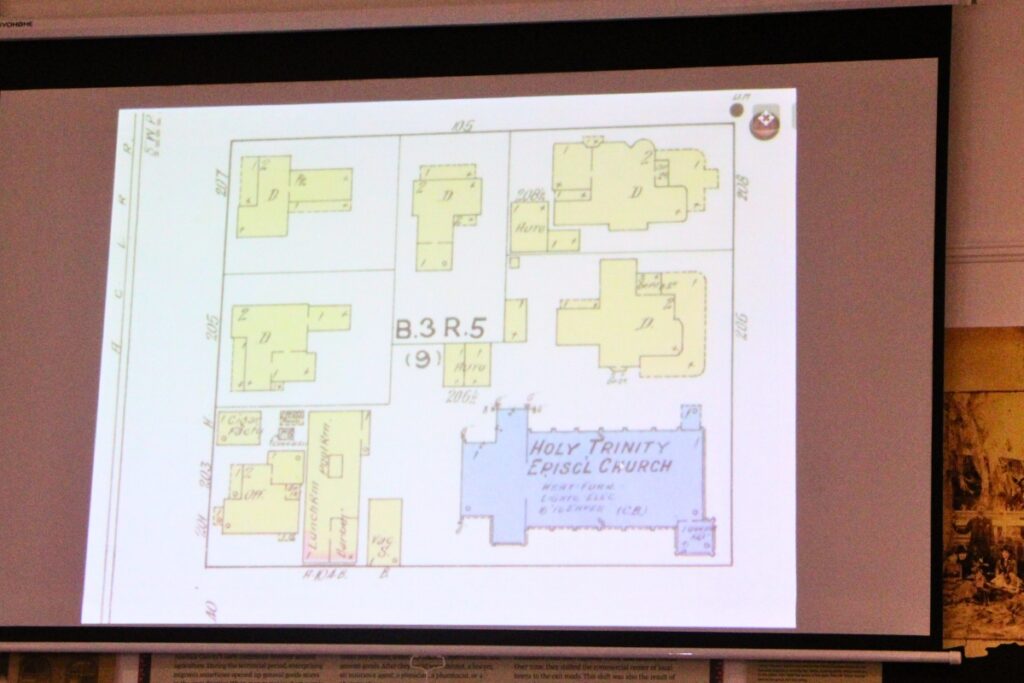

The Holy Trinity Episcopal Foundation (HTEF) of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church (HTEC) owns the three buildings planned for demolition and the block they’re built on facing Main Street.

The three buildings are the former Barton Thrasher/Barton Douglas law office (103 N. Main St.) and the former The Wine and Cheese Gallery building (113 N. Main St.)—both circa 1879—as well as the art deco-style and former Modern Shoe Repair building (101 N. Main St.) that turns 100 years old next year.

HTEF acquired segments of the block in 2001, 2012 and 2014 for the “use and benefit of Holy Trinity Parish,” according to a handout at the presentation. The nonprofit recently filed for a demolition permit, claiming the buildings are too run-down and expensive to restore and have become a site for homeless individuals.

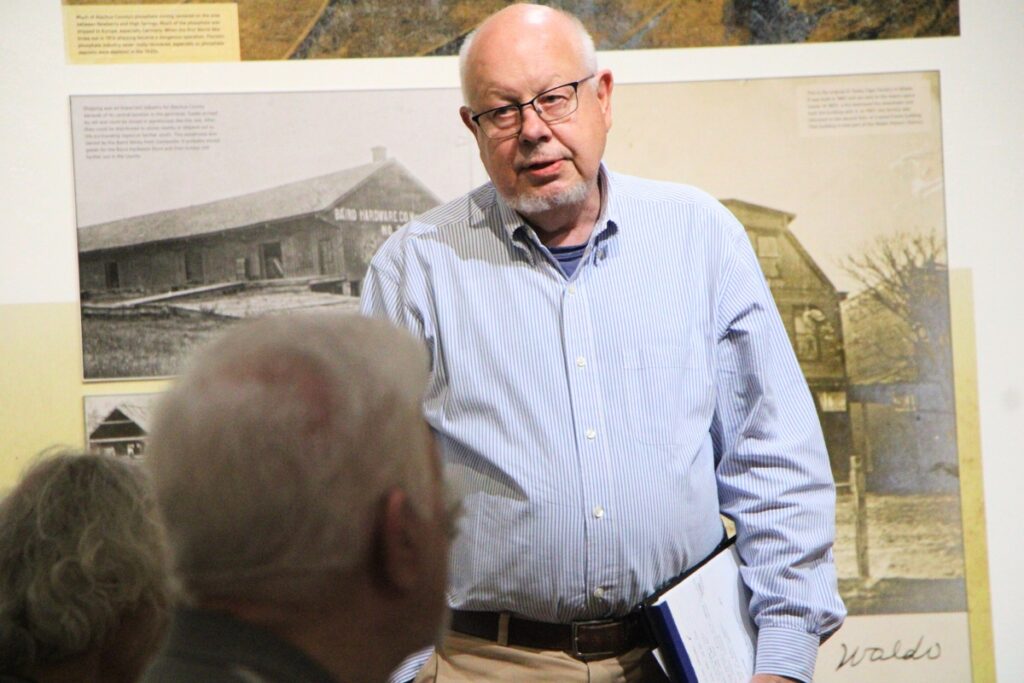

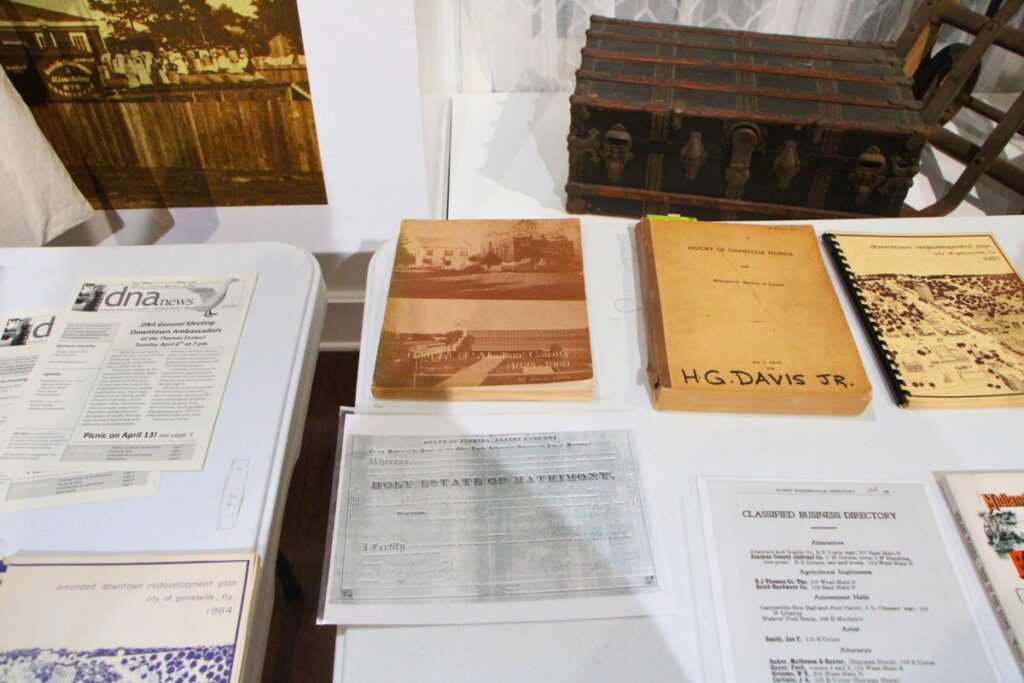

Historic preservation advocate Melanie Barr researched the block and the three buildings to lead Wednesday’s presentation detailing their significance in terms of age, architecture and the people that lived and worked in them for context of why they shouldn’t be torn down.

Civil War veteran and three-time Gainesville mayor James Brown used to own the block in the 19th century and local rock icons Stephen Stills and Tom Petty—who was married at HTEC—frequented the block.

Since two of the three buildings are some of the few that survived the fires of the 1880’s, Barr said the city will lose one of its most historic areas, if demolished.

“Don’t destroy our history, it can’t come back,” she said. “I’m really hoping we don’t destroy buildings to celebrate our [Alachua County] bicentennial.”

Although the buildings are privately owned by HTEF, Barr suggested alternative solutions to demolition. She said if a private individual invested the money for renovations up front, they could take advantage of federal and state programs and tax exemptions to pay off the debt.

Barr also appealed to the city commission to invest in preserving the block in order to uphold their master plans and development standards for the city.

Barr said one city commissioner she invited did not show up because they believed preserving the privately-owned buildings was not a city issue since they don’t fall within the designated historic district or have historical markers.

“Gainesville’s vision is to have a live, vibrant downtown and a strong, resilient economy,” Barr said. “I don’t think you can have a vibrant or alive downtown with a vacant lot, and that’s what’s going to happen for some years.”

Tensions escalated in the Matheson following Barr’s presentation as HTEF president Brian Gendreau stood up in the audience of preservationists to defend the church’s demolition plan.

Gendreau also distributed copies of an April 5 email he wrote to Duckpond Neighborhood Association president Wes Jones, addressing concerns Jones had expressed about demolishing the buildings.

Barr originally told him he couldn’t speak as the meeting was private for historic preservationist supporters, but allowed the dialogue to continue.

Gendreau said the church had been considering demolishing the buildings for the last three years. He said they’ve already spent five figures ridding the buildings of asbestos and the foundations have been destroyed by termites and dry rot.

In his email to Jones, Gendreau wrote that the buildings on North Main Street do not serve the needs of the HTEC congregation, are not economically feasible to renovate, threaten public safety and are a “blight to the downtown area.”

He said HTEF hired a consulting firm that estimated it would take $1 million to restore the former law office and remove its lead paint, as opposed to $288,000 to demolish the buildings.

Gendreau said the church had renovated buildings on its property before, such as when the congregation put over $1.5 million into the Holy Trinity Episcopal School of Gainesville. But HTEF has already consulted with professionals to properly dispose of materials from the site and with GRU to terminate utility services.

Gendreau also said that because the buildings are vacant due to their condition, the nonprofit can’t insure the buildings, which he said weren’t built for commercial use, although he wrote in his email that they were built for commercial use.

Gendreau also wrote in his email that the buildings on North Main Street are “not historic.” However, he also wrote that HTEF is planning to prepare a photo journal “for the purpose of documenting the structures” that will be offered to the public library and the Matheson History Museum.

Resident and local realtor Michelle Hazen said the only reason the buildings are in the condition they’re in is that they’ve been neglected. She said every old property comes with maintenance and HTEF wouldn’t have to demolish the buildings if they had been properly stewarded and taken care of from the beginning.

“You’ve chosen as a church to purchase these buildings and then not maintain them,” Hazen said. “It’s pure demolition by neglect…and that’s a choice, but at this point in time, it changes the fabric of our downtown.”

Hazen also said that even if it’s too late to save the three buildings on North Main Street, citizens should continue fighting to save historic properties from being torn down by voicing their concerns at preservation and commission meetings.

Resident David Hammer asked what the church’s intentions were when HTEF originally purchased the buildings and what they intend to do with the land once they’re gone.

Gendreau answered that the church intends to put in a park with a stone wall it could use for events like wedding ceremonies and also add more parking.

He wrote in his email that HTEF had already sought out wall and fence companies to place a temporary and permanent wall and metal fence around the property for public safety.

Hammer also brought up HTEF’s history of buying land with historic buildings on it and demolishing the properties.

In 2018, the Gainesville Sun reported that the Episcopal Diocese of Florida tore down St. Michael’s Episcopal Parish (4315 NW 23rd Ave.)—citing a similar state of disrepair as the North Main Street properties—one week before a meeting that could have designated the building as a historic landmark.

“There’s an awful lot of concern and angst about the Episcopal Diocese of North Florida in this community already,” Hammer said. “Do you really want to continue this course of action and go down in history as the church that destroyed historic buildings? Because that’s the chapter that you’re about to write, potentially.”

When residents asked why the church didn’t offer to sell the buildings to someone who would be able to restore them, Gendreau said the church had put them up for sale but never placed signs out front saying so.

When asked whether the church had been paying taxes on the buildings or received tax exemptions, Gendreau said, “There’s no reason to pay taxes on them.”

After both Gendreau and the residents said he had outstayed his welcome, Barr ended the meeting.

As of Thursday, an orange sign placed outside the 103 N. Main Street building says:

“Notice: Free building to anyone who pays to have it moved. Contact the City of Gainesville Historic Preservation at (352) 393-8686 or hpb@cityofgainesville.org who will refer you to the owner. Please do not bother the residents they will not have any answers to your questions. Please hurry! Demolition will happen soon! Do not tamper or damage under threat of civil penalty.”

Thank you, Lillian and Mainstreet, for covering the presentation and this important story.